The Politics of Memory

Genocide Memorials in Rwanda

"'...The people who did this,' he said, 'thought that whatever happened, nobody would know. It didn't matter, because they would kill everybody, and there would be nothing to see.'

I kept looking then, out of defiance."

--Philip Gourevitch

Tracking mountain gorillas is the most lucrative and popular Rwandan tourist attraction. After emerging from the quiet northern forests, however, tourists who remain a little longer confront a dry landscape teeming with human difficulties. The second most common tourist attraction in Rwanda is the genocide memorial.

Color Codes

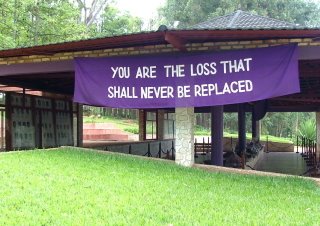

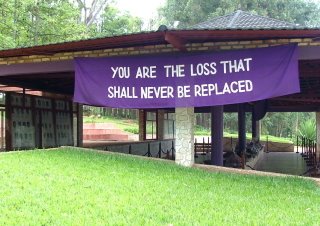

No one can travel far in Rwanda without seeing purple and pink.

Purple drapes a slew of genocide memorials: purple banners, purple flags, purple signs, purple flowers. The Rwandan government has taken radical action to prevent genocide denial, and one of their most visible strategies has been establishing codified monuments to the hundreds of thousands of people slaughtered in 1994. Purple appears suddenly around a bend, or through a thick row of trees, to remind the ordinary traveler that this is no ordinary place. Purple is a linguistic signifier, voicing the unspeakable. It represents the hope that Rwandan history is no longer to be regarded only as a capsizable chronicle of finite events. Purple reminds us that endings are, generally, to be resisted.

signs, purple flowers. The Rwandan government has taken radical action to prevent genocide denial, and one of their most visible strategies has been establishing codified monuments to the hundreds of thousands of people slaughtered in 1994. Purple appears suddenly around a bend, or through a thick row of trees, to remind the ordinary traveler that this is no ordinary place. Purple is a linguistic signifier, voicing the unspeakable. It represents the hope that Rwandan history is no longer to be regarded only as a capsizable chronicle of finite events. Purple reminds us that endings are, generally, to be resisted.

Pink drapes the bodies of those who are accused of genocide crimes. Prison uniforms in Rwanda are a cheerful bubblegum color. Truckloads of men walk around in pink shirts and shorts, shaded with pink baseball caps, working tranquilly. The accused work on public service projects until their trials, which are always years away. They build houses, arrange greenery, till the soil, plant seedlings, and wave at passers-by, inexplicable bits of cotton candy in a careful landscape. Pink is the reverse of purple. It is the eraser, the clean up crew.

False Sanctuaries

The majority of memorials are plain old lumps of buildings dedicated to the memory of extraordinary events. The genocide turned logic on its head. The largest massacres took place in ordinary spaces - churches, schools, hospitals, and orphanages - where the victims had gathered for safety. Many of these structures still sit silently on their foundations, absorbed by trees.

The Kibuye memorial church is one of the many churches in Rwanda that has been restored to a functioning place of worship. The brooding stone edifice perches high on a cliff, overlooking the main road into town. The stained glass windows, once blown out by grenades, have been replaced by mosaics of lively colors. Boys have footraces in the front yard, and the church choir rehearses on weekends. In most scholarly accounts, Kibuye is mentioned as one of the most decimated provinces, and the Kibuye church massacre tops many a list of unthinkable acts - over eleven thousand Tutsis flocked to the church, and all were slaughtered within a matter of days.

on a cliff, overlooking the main road into town. The stained glass windows, once blown out by grenades, have been replaced by mosaics of lively colors. Boys have footraces in the front yard, and the church choir rehearses on weekends. In most scholarly accounts, Kibuye is mentioned as one of the most decimated provinces, and the Kibuye church massacre tops many a list of unthinkable acts - over eleven thousand Tutsis flocked to the church, and all were slaughtered within a matter of days.

Butare is another location that ranks high in offcial death tallies. When the genocide began, there were hopes that this province, the site of the National University of Rwanda and Rwanda's intellectual stronghold, would be exempt from the massive killings that were taking place in the rest of the country. For the first two weeks of the genocide, people flocked to the region, hoping to escape the worst of the madness. The reprieve didn't last long. After the initial quiet, Butare quickly became one of the worst hit regions as militias were trucked in from already stripped areas to finish their work.

The university's memorial is another extraordinary quiet place, nestled among rows of thin trees. Under a pavilion, photographs of murdered students and teachers stare down at visitors from glass cases. Most are smiling shyly for their yearbook photos, a reminder of the era that Rwandans occasionally refer to as Before.

Corporeal Displays

"The aesthetic assault of the macabre creates excitement and emotion, but does the spectacle really serve our understanding of the wrong?"

--Philip Gourevitch

Another type of genocide memorial in Rwanda is one that displays the physical evidence of the crime: bones, graves, clothing, or bodies. These memorials in particular bait all the huge questions -- how to prevent this from happening again, how to educate outsiders, how to grieve properly, even how to remember correctly. If they have been unnaturally taken, Elie Wiesel notes, the dead must rely on the living to defend them. But how do the living balance all of these issues?

In a whispered tribute to the European Catholic tradition, several Rwandan churches have skulls and bones displayed as a memorial, as in this example from the church in Kibuye. Some bones are gathered into tidy piles, and sometimes they are scattered chaotically, where they fell. Some memorial staff stack the skulls from their communities into careful pyramids, sockets arranged in billiard triangles.

One memorial does not stop with bones. During the genocide, fifty thousand people sought shelter at the school in Murambi and all were slaughtered in its classrooms. In 1995, fifty thousand mummified bodies were exhumed from nearby mass graves and placed on display.

Murambi is a controversial place. The debate rages over whether such a graphic display is an appropriate tribute, and whose consent was given to create it. Not everyone is convinced that the dead would want to be remembered in their state of vulnerability.

A guide led me around this endless labyrinth of rooms, chatting politely. The Murambi memorial was created only a few months after the war was over. It was a direct response to international denial that a genocide had taken place in Rwanda. Oh, in particular the Mitterand government. No, since the massacre, the school has never been finished. It looks just as it did during the killings. Yes, he was from the area. Yes, he had survived in hiding, but many of his family members had not. He did not know if his mother and brother were among the dead at Murambi because it is impossible to recognize the faces after eleven years of exposure to air. Yes, he chose this job. Why? People need to see who were not here.

The first door opened. The bodies were white with lime, twisted, mummified. The smell revisits me. I did not make it through all 64 rooms.

The first door opened. The bodies were white with lime, twisted, mummified. The smell revisits me. I did not make it through all 64 rooms.

As moving, and much less contentious, is the display of the victims' clothes at Murambi. In a larger building, still on the school grounds, three clotheslines stretch across a unfinished space with the feel of an abandoned warehouse. The lines are heaped with all of the muddy, rotting clothes that were collected from the exhumed bodies. The display is simple, artistically presented, as stylized as a Soho gallery, and as shocking in volume as in starkness.

The lines are heaped with all of the muddy, rotting clothes that were collected from the exhumed bodies. The display is simple, artistically presented, as stylized as a Soho gallery, and as shocking in volume as in starkness.

And Words?

Words are too often not enough. In Butare, they are:

"'...The people who did this,' he said, 'thought that whatever happened, nobody would know. It didn't matter, because they would kill everybody, and there would be nothing to see.'

I kept looking then, out of defiance."

--Philip Gourevitch

Tracking mountain gorillas is the most lucrative and popular Rwandan tourist attraction. After emerging from the quiet northern forests, however, tourists who remain a little longer confront a dry landscape teeming with human difficulties. The second most common tourist attraction in Rwanda is the genocide memorial.

Color Codes

No one can travel far in Rwanda without seeing purple and pink.

Purple drapes a slew of genocide memorials: purple banners, purple flags, purple

signs, purple flowers. The Rwandan government has taken radical action to prevent genocide denial, and one of their most visible strategies has been establishing codified monuments to the hundreds of thousands of people slaughtered in 1994. Purple appears suddenly around a bend, or through a thick row of trees, to remind the ordinary traveler that this is no ordinary place. Purple is a linguistic signifier, voicing the unspeakable. It represents the hope that Rwandan history is no longer to be regarded only as a capsizable chronicle of finite events. Purple reminds us that endings are, generally, to be resisted.

signs, purple flowers. The Rwandan government has taken radical action to prevent genocide denial, and one of their most visible strategies has been establishing codified monuments to the hundreds of thousands of people slaughtered in 1994. Purple appears suddenly around a bend, or through a thick row of trees, to remind the ordinary traveler that this is no ordinary place. Purple is a linguistic signifier, voicing the unspeakable. It represents the hope that Rwandan history is no longer to be regarded only as a capsizable chronicle of finite events. Purple reminds us that endings are, generally, to be resisted.Pink drapes the bodies of those who are accused of genocide crimes. Prison uniforms in Rwanda are a cheerful bubblegum color. Truckloads of men walk around in pink shirts and shorts, shaded with pink baseball caps, working tranquilly. The accused work on public service projects until their trials, which are always years away. They build houses, arrange greenery, till the soil, plant seedlings, and wave at passers-by, inexplicable bits of cotton candy in a careful landscape. Pink is the reverse of purple. It is the eraser, the clean up crew.

False Sanctuaries

The majority of memorials are plain old lumps of buildings dedicated to the memory of extraordinary events. The genocide turned logic on its head. The largest massacres took place in ordinary spaces - churches, schools, hospitals, and orphanages - where the victims had gathered for safety. Many of these structures still sit silently on their foundations, absorbed by trees.

The Kibuye memorial church is one of the many churches in Rwanda that has been restored to a functioning place of worship. The brooding stone edifice perches high

on a cliff, overlooking the main road into town. The stained glass windows, once blown out by grenades, have been replaced by mosaics of lively colors. Boys have footraces in the front yard, and the church choir rehearses on weekends. In most scholarly accounts, Kibuye is mentioned as one of the most decimated provinces, and the Kibuye church massacre tops many a list of unthinkable acts - over eleven thousand Tutsis flocked to the church, and all were slaughtered within a matter of days.

on a cliff, overlooking the main road into town. The stained glass windows, once blown out by grenades, have been replaced by mosaics of lively colors. Boys have footraces in the front yard, and the church choir rehearses on weekends. In most scholarly accounts, Kibuye is mentioned as one of the most decimated provinces, and the Kibuye church massacre tops many a list of unthinkable acts - over eleven thousand Tutsis flocked to the church, and all were slaughtered within a matter of days.Butare is another location that ranks high in offcial death tallies. When the genocide began, there were hopes that this province, the site of the National University of Rwanda and Rwanda's intellectual stronghold, would be exempt from the massive killings that were taking place in the rest of the country. For the first two weeks of the genocide, people flocked to the region, hoping to escape the worst of the madness. The reprieve didn't last long. After the initial quiet, Butare quickly became one of the worst hit regions as militias were trucked in from already stripped areas to finish their work.

The university's memorial is another extraordinary quiet place, nestled among rows of thin trees. Under a pavilion, photographs of murdered students and teachers stare down at visitors from glass cases. Most are smiling shyly for their yearbook photos, a reminder of the era that Rwandans occasionally refer to as Before.

Corporeal Displays

"The aesthetic assault of the macabre creates excitement and emotion, but does the spectacle really serve our understanding of the wrong?"

--Philip Gourevitch

Another type of genocide memorial in Rwanda is one that displays the physical evidence of the crime: bones, graves, clothing, or bodies. These memorials in particular bait all the huge questions -- how to prevent this from happening again, how to educate outsiders, how to grieve properly, even how to remember correctly. If they have been unnaturally taken, Elie Wiesel notes, the dead must rely on the living to defend them. But how do the living balance all of these issues?

In a whispered tribute to the European Catholic tradition, several Rwandan churches have skulls and bones displayed as a memorial, as in this example from the church in Kibuye. Some bones are gathered into tidy piles, and sometimes they are scattered chaotically, where they fell. Some memorial staff stack the skulls from their communities into careful pyramids, sockets arranged in billiard triangles.

One memorial does not stop with bones. During the genocide, fifty thousand people sought shelter at the school in Murambi and all were slaughtered in its classrooms. In 1995, fifty thousand mummified bodies were exhumed from nearby mass graves and placed on display.

Murambi is a controversial place. The debate rages over whether such a graphic display is an appropriate tribute, and whose consent was given to create it. Not everyone is convinced that the dead would want to be remembered in their state of vulnerability.

A guide led me around this endless labyrinth of rooms, chatting politely. The Murambi memorial was created only a few months after the war was over. It was a direct response to international denial that a genocide had taken place in Rwanda. Oh, in particular the Mitterand government. No, since the massacre, the school has never been finished. It looks just as it did during the killings. Yes, he was from the area. Yes, he had survived in hiding, but many of his family members had not. He did not know if his mother and brother were among the dead at Murambi because it is impossible to recognize the faces after eleven years of exposure to air. Yes, he chose this job. Why? People need to see who were not here.

The first door opened. The bodies were white with lime, twisted, mummified. The smell revisits me. I did not make it through all 64 rooms.

The first door opened. The bodies were white with lime, twisted, mummified. The smell revisits me. I did not make it through all 64 rooms. As moving, and much less contentious, is the display of the victims' clothes at Murambi. In a larger building, still on the school grounds, three clotheslines stretch across a unfinished space with the feel of an abandoned warehouse.

The lines are heaped with all of the muddy, rotting clothes that were collected from the exhumed bodies. The display is simple, artistically presented, as stylized as a Soho gallery, and as shocking in volume as in starkness.

The lines are heaped with all of the muddy, rotting clothes that were collected from the exhumed bodies. The display is simple, artistically presented, as stylized as a Soho gallery, and as shocking in volume as in starkness.And Words?

Words are too often not enough. In Butare, they are:

<< Home