Friday, March 24, 2006

The Politics of Memory

Genocide Memorials in Rwanda

"'...The people who did this,' he said, 'thought that whatever happened, nobody would know. It didn't matter, because they would kill everybody, and there would be nothing to see.'

I kept looking then, out of defiance."

--Philip Gourevitch

Tracking mountain gorillas is the most lucrative and popular Rwandan tourist attraction. After emerging from the quiet northern forests, however, tourists who remain a little longer confront a dry landscape teeming with human difficulties. The second most common tourist attraction in Rwanda is the genocide memorial.

Color Codes

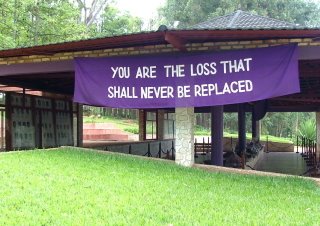

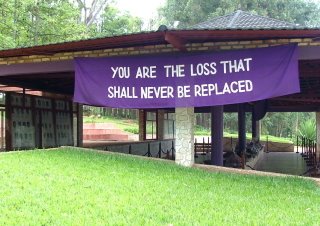

No one can travel far in Rwanda without seeing purple and pink.

Purple drapes a slew of genocide memorials: purple banners, purple flags, purple signs, purple flowers. The Rwandan government has taken radical action to prevent genocide denial, and one of their most visible strategies has been establishing codified monuments to the hundreds of thousands of people slaughtered in 1994. Purple appears suddenly around a bend, or through a thick row of trees, to remind the ordinary traveler that this is no ordinary place. Purple is a linguistic signifier, voicing the unspeakable. It represents the hope that Rwandan history is no longer to be regarded only as a capsizable chronicle of finite events. Purple reminds us that endings are, generally, to be resisted.

signs, purple flowers. The Rwandan government has taken radical action to prevent genocide denial, and one of their most visible strategies has been establishing codified monuments to the hundreds of thousands of people slaughtered in 1994. Purple appears suddenly around a bend, or through a thick row of trees, to remind the ordinary traveler that this is no ordinary place. Purple is a linguistic signifier, voicing the unspeakable. It represents the hope that Rwandan history is no longer to be regarded only as a capsizable chronicle of finite events. Purple reminds us that endings are, generally, to be resisted.

Pink drapes the bodies of those who are accused of genocide crimes. Prison uniforms in Rwanda are a cheerful bubblegum color. Truckloads of men walk around in pink shirts and shorts, shaded with pink baseball caps, working tranquilly. The accused work on public service projects until their trials, which are always years away. They build houses, arrange greenery, till the soil, plant seedlings, and wave at passers-by, inexplicable bits of cotton candy in a careful landscape. Pink is the reverse of purple. It is the eraser, the clean up crew.

False Sanctuaries

The majority of memorials are plain old lumps of buildings dedicated to the memory of extraordinary events. The genocide turned logic on its head. The largest massacres took place in ordinary spaces - churches, schools, hospitals, and orphanages - where the victims had gathered for safety. Many of these structures still sit silently on their foundations, absorbed by trees.

The Kibuye memorial church is one of the many churches in Rwanda that has been restored to a functioning place of worship. The brooding stone edifice perches high on a cliff, overlooking the main road into town. The stained glass windows, once blown out by grenades, have been replaced by mosaics of lively colors. Boys have footraces in the front yard, and the church choir rehearses on weekends. In most scholarly accounts, Kibuye is mentioned as one of the most decimated provinces, and the Kibuye church massacre tops many a list of unthinkable acts - over eleven thousand Tutsis flocked to the church, and all were slaughtered within a matter of days.

on a cliff, overlooking the main road into town. The stained glass windows, once blown out by grenades, have been replaced by mosaics of lively colors. Boys have footraces in the front yard, and the church choir rehearses on weekends. In most scholarly accounts, Kibuye is mentioned as one of the most decimated provinces, and the Kibuye church massacre tops many a list of unthinkable acts - over eleven thousand Tutsis flocked to the church, and all were slaughtered within a matter of days.

Butare is another location that ranks high in offcial death tallies. When the genocide began, there were hopes that this province, the site of the National University of Rwanda and Rwanda's intellectual stronghold, would be exempt from the massive killings that were taking place in the rest of the country. For the first two weeks of the genocide, people flocked to the region, hoping to escape the worst of the madness. The reprieve didn't last long. After the initial quiet, Butare quickly became one of the worst hit regions as militias were trucked in from already stripped areas to finish their work.

The university's memorial is another extraordinary quiet place, nestled among rows of thin trees. Under a pavilion, photographs of murdered students and teachers stare down at visitors from glass cases. Most are smiling shyly for their yearbook photos, a reminder of the era that Rwandans occasionally refer to as Before.

Corporeal Displays

"The aesthetic assault of the macabre creates excitement and emotion, but does the spectacle really serve our understanding of the wrong?"

--Philip Gourevitch

Another type of genocide memorial in Rwanda is one that displays the physical evidence of the crime: bones, graves, clothing, or bodies. These memorials in particular bait all the huge questions -- how to prevent this from happening again, how to educate outsiders, how to grieve properly, even how to remember correctly. If they have been unnaturally taken, Elie Wiesel notes, the dead must rely on the living to defend them. But how do the living balance all of these issues?

In a whispered tribute to the European Catholic tradition, several Rwandan churches have skulls and bones displayed as a memorial, as in this example from the church in Kibuye. Some bones are gathered into tidy piles, and sometimes they are scattered chaotically, where they fell. Some memorial staff stack the skulls from their communities into careful pyramids, sockets arranged in billiard triangles.

One memorial does not stop with bones. During the genocide, fifty thousand people sought shelter at the school in Murambi and all were slaughtered in its classrooms. In 1995, fifty thousand mummified bodies were exhumed from nearby mass graves and placed on display.

Murambi is a controversial place. The debate rages over whether such a graphic display is an appropriate tribute, and whose consent was given to create it. Not everyone is convinced that the dead would want to be remembered in their state of vulnerability.

A guide led me around this endless labyrinth of rooms, chatting politely. The Murambi memorial was created only a few months after the war was over. It was a direct response to international denial that a genocide had taken place in Rwanda. Oh, in particular the Mitterand government. No, since the massacre, the school has never been finished. It looks just as it did during the killings. Yes, he was from the area. Yes, he had survived in hiding, but many of his family members had not. He did not know if his mother and brother were among the dead at Murambi because it is impossible to recognize the faces after eleven years of exposure to air. Yes, he chose this job. Why? People need to see who were not here.

The first door opened. The bodies were white with lime, twisted, mummified. The smell revisits me. I did not make it through all 64 rooms.

The first door opened. The bodies were white with lime, twisted, mummified. The smell revisits me. I did not make it through all 64 rooms.

As moving, and much less contentious, is the display of the victims' clothes at Murambi. In a larger building, still on the school grounds, three clotheslines stretch across a unfinished space with the feel of an abandoned warehouse. The lines are heaped with all of the muddy, rotting clothes that were collected from the exhumed bodies. The display is simple, artistically presented, as stylized as a Soho gallery, and as shocking in volume as in starkness.

The lines are heaped with all of the muddy, rotting clothes that were collected from the exhumed bodies. The display is simple, artistically presented, as stylized as a Soho gallery, and as shocking in volume as in starkness.

And Words?

Words are too often not enough. In Butare, they are:

"'...The people who did this,' he said, 'thought that whatever happened, nobody would know. It didn't matter, because they would kill everybody, and there would be nothing to see.'

I kept looking then, out of defiance."

--Philip Gourevitch

Tracking mountain gorillas is the most lucrative and popular Rwandan tourist attraction. After emerging from the quiet northern forests, however, tourists who remain a little longer confront a dry landscape teeming with human difficulties. The second most common tourist attraction in Rwanda is the genocide memorial.

Color Codes

No one can travel far in Rwanda without seeing purple and pink.

Purple drapes a slew of genocide memorials: purple banners, purple flags, purple

signs, purple flowers. The Rwandan government has taken radical action to prevent genocide denial, and one of their most visible strategies has been establishing codified monuments to the hundreds of thousands of people slaughtered in 1994. Purple appears suddenly around a bend, or through a thick row of trees, to remind the ordinary traveler that this is no ordinary place. Purple is a linguistic signifier, voicing the unspeakable. It represents the hope that Rwandan history is no longer to be regarded only as a capsizable chronicle of finite events. Purple reminds us that endings are, generally, to be resisted.

signs, purple flowers. The Rwandan government has taken radical action to prevent genocide denial, and one of their most visible strategies has been establishing codified monuments to the hundreds of thousands of people slaughtered in 1994. Purple appears suddenly around a bend, or through a thick row of trees, to remind the ordinary traveler that this is no ordinary place. Purple is a linguistic signifier, voicing the unspeakable. It represents the hope that Rwandan history is no longer to be regarded only as a capsizable chronicle of finite events. Purple reminds us that endings are, generally, to be resisted.Pink drapes the bodies of those who are accused of genocide crimes. Prison uniforms in Rwanda are a cheerful bubblegum color. Truckloads of men walk around in pink shirts and shorts, shaded with pink baseball caps, working tranquilly. The accused work on public service projects until their trials, which are always years away. They build houses, arrange greenery, till the soil, plant seedlings, and wave at passers-by, inexplicable bits of cotton candy in a careful landscape. Pink is the reverse of purple. It is the eraser, the clean up crew.

False Sanctuaries

The majority of memorials are plain old lumps of buildings dedicated to the memory of extraordinary events. The genocide turned logic on its head. The largest massacres took place in ordinary spaces - churches, schools, hospitals, and orphanages - where the victims had gathered for safety. Many of these structures still sit silently on their foundations, absorbed by trees.

The Kibuye memorial church is one of the many churches in Rwanda that has been restored to a functioning place of worship. The brooding stone edifice perches high

on a cliff, overlooking the main road into town. The stained glass windows, once blown out by grenades, have been replaced by mosaics of lively colors. Boys have footraces in the front yard, and the church choir rehearses on weekends. In most scholarly accounts, Kibuye is mentioned as one of the most decimated provinces, and the Kibuye church massacre tops many a list of unthinkable acts - over eleven thousand Tutsis flocked to the church, and all were slaughtered within a matter of days.

on a cliff, overlooking the main road into town. The stained glass windows, once blown out by grenades, have been replaced by mosaics of lively colors. Boys have footraces in the front yard, and the church choir rehearses on weekends. In most scholarly accounts, Kibuye is mentioned as one of the most decimated provinces, and the Kibuye church massacre tops many a list of unthinkable acts - over eleven thousand Tutsis flocked to the church, and all were slaughtered within a matter of days.Butare is another location that ranks high in offcial death tallies. When the genocide began, there were hopes that this province, the site of the National University of Rwanda and Rwanda's intellectual stronghold, would be exempt from the massive killings that were taking place in the rest of the country. For the first two weeks of the genocide, people flocked to the region, hoping to escape the worst of the madness. The reprieve didn't last long. After the initial quiet, Butare quickly became one of the worst hit regions as militias were trucked in from already stripped areas to finish their work.

The university's memorial is another extraordinary quiet place, nestled among rows of thin trees. Under a pavilion, photographs of murdered students and teachers stare down at visitors from glass cases. Most are smiling shyly for their yearbook photos, a reminder of the era that Rwandans occasionally refer to as Before.

Corporeal Displays

"The aesthetic assault of the macabre creates excitement and emotion, but does the spectacle really serve our understanding of the wrong?"

--Philip Gourevitch

Another type of genocide memorial in Rwanda is one that displays the physical evidence of the crime: bones, graves, clothing, or bodies. These memorials in particular bait all the huge questions -- how to prevent this from happening again, how to educate outsiders, how to grieve properly, even how to remember correctly. If they have been unnaturally taken, Elie Wiesel notes, the dead must rely on the living to defend them. But how do the living balance all of these issues?

In a whispered tribute to the European Catholic tradition, several Rwandan churches have skulls and bones displayed as a memorial, as in this example from the church in Kibuye. Some bones are gathered into tidy piles, and sometimes they are scattered chaotically, where they fell. Some memorial staff stack the skulls from their communities into careful pyramids, sockets arranged in billiard triangles.

One memorial does not stop with bones. During the genocide, fifty thousand people sought shelter at the school in Murambi and all were slaughtered in its classrooms. In 1995, fifty thousand mummified bodies were exhumed from nearby mass graves and placed on display.

Murambi is a controversial place. The debate rages over whether such a graphic display is an appropriate tribute, and whose consent was given to create it. Not everyone is convinced that the dead would want to be remembered in their state of vulnerability.

A guide led me around this endless labyrinth of rooms, chatting politely. The Murambi memorial was created only a few months after the war was over. It was a direct response to international denial that a genocide had taken place in Rwanda. Oh, in particular the Mitterand government. No, since the massacre, the school has never been finished. It looks just as it did during the killings. Yes, he was from the area. Yes, he had survived in hiding, but many of his family members had not. He did not know if his mother and brother were among the dead at Murambi because it is impossible to recognize the faces after eleven years of exposure to air. Yes, he chose this job. Why? People need to see who were not here.

The first door opened. The bodies were white with lime, twisted, mummified. The smell revisits me. I did not make it through all 64 rooms.

The first door opened. The bodies were white with lime, twisted, mummified. The smell revisits me. I did not make it through all 64 rooms. As moving, and much less contentious, is the display of the victims' clothes at Murambi. In a larger building, still on the school grounds, three clotheslines stretch across a unfinished space with the feel of an abandoned warehouse.

The lines are heaped with all of the muddy, rotting clothes that were collected from the exhumed bodies. The display is simple, artistically presented, as stylized as a Soho gallery, and as shocking in volume as in starkness.

The lines are heaped with all of the muddy, rotting clothes that were collected from the exhumed bodies. The display is simple, artistically presented, as stylized as a Soho gallery, and as shocking in volume as in starkness.And Words?

Words are too often not enough. In Butare, they are:

Friday, March 03, 2006

Electric Green Lines

Tea Growing in Rwanda

Tea is one of Rwanda's primary exports and most valuable cash crops. Outside Nyungwe Forest is the rolling Gisakura tea plantation. Acres of undulating farmland are billowy with electric green tea bushes, and fog lines the tops of hills. Every field is partially fallow, so the bushes form geometric patterns of green and brown.

Tea is one of Rwanda's primary exports and most valuable cash crops. Outside Nyungwe Forest is the rolling Gisakura tea plantation. Acres of undulating farmland are billowy with electric green tea bushes, and fog lines the tops of hills. Every field is partially fallow, so the bushes form geometric patterns of green and brown.

"The Most Elusive of Primates"

The Author Goes Chimpanzee Tracking in Nyungwe Forest

The most obvious reason to visit Rwanda is to see the world's most fascinating primates in their natural habitat - a quixotic quest if ever I've experienced one. For anyone with a few days to spare after tracking mountain gorillas, Nyungwe Forest offers a small primate B-side.

Monkeys are the most visible residents of the forest. Families of L'Hoest monkeys pick through vines in the roadside tangles of brush, and a troop of Colobus monkeys on the nearby tea estate has been habituated to refrain from fleeing when park visitors come crashing through the undergrowth.

Monkeys are the most visible residents of the forest. Families of L'Hoest monkeys pick through vines in the roadside tangles of brush, and a troop of Colobus monkeys on the nearby tea estate has been habituated to refrain from fleeing when park visitors come crashing through the undergrowth.

But chimpanzees are the attraction that draws most primate-watchers to Nyungwe. For seventy US dollars, you can attempt to track them with the help of a guide, a handful of trackers, and a walkie-talkie. This experience is best suited for hikers who feel a twinge of excitement at the thought of waking up at 4:30 am, scrambling around a rainforest in pursuit of the most elusive of primates, and emerging from a green world, half a day later, crippled and completely covered with mud.

Chimp treks differ from normal Nyungwe hikes because there are no pre-cut trails that allow you to follow the chimps' erratic movements. The terrain is extremely steep; and because Nyungwe is a true rainforest, the ground cover is both exceptionally dense and sopping wet. The result is an experience that, when retold in later company, sounds like a journal entry of an early American pioneer: the journey was muddy, daunting, backbreaking, and occasionally meaningful.

A tracker with a machete begins the procession, hacking through the thickest vines and branches. The guide follows, indicating which entrances to small mammal burrows could potentially snap a leg if accidentally plunged into. Civilian hikers bring up the rear, wielding long, thin walking sticks. They plunge through thick curtains of ferns, ducking under vines, climbing over fallen tree trunks, ice-skating across the slippery sides of the hills, all the while trying to ignore the furry white caterpillars, black beetles, and other unnaturally large insects resting on the leaves that brush over their faces and necks.

Traveling with speed is, unfortunately, impossible. Therein lies the challenge. Chimps prefer to take their breakfast in the valleys that lie between hills. They will tolerate the presence of a tracker or two; but when the number of gawkers rises above comfort level, they swing over to the next valley, floating through the mountain treetops as effortlessly as butterflies.

Humans are a hopelessly grounded species. When the chimps disappear over the top of the next mountain, the only way to follow is to crawl up and down the hills in sluggish, groaning pursuit. The uphill slopes are steep enough that you can touch your nose to the trail without leaning forward more than a foot. Grabbing vines and pulling yourself up is the only way to steady your climb when the mud gives way.

Uphill may be slow and strenuous, but downhill makes people fall. Cover a wall in your house with vines and mud, and then walk down it. If you can do it without bruising the end of your spine when you slip, or overextending leg muscles when one foot gets hung up in the foliage and the other slides out from under you, then chimp tracking will come naturally to you.

After four hours of climbing, sliding, falling, and being scratched by thorns, all the while hearing the screams of chimps around every next bend, the front tracker informed our group for the tenth time that we had just missed them. We mutinied. How were six people hacking through brush ever going to sneak up on such quick animals? We wanted to turn back, we declared. Because park policy is to refund the tracking fee if no chimps are spotted, the guides huddled and began to whisper. After a few minutes, one of them assured us that if we did not see a chimp around the next bend, we would turn back. We were a group of strangers thrown together in the woods, and we did not have a unity of purpose. No one wanted to be the wimp who made everyone turn back twenty minutes too early. We set off again.

Another stretch down, more slipping, more thorns. The guide behind me fell and took me out. Like amateur skiers, we both tumbled down to the swampy creek at the bottom. Then another aching uphill. A vine I grabbed ripped out of the ground and sent me flailing backwards for a few yards.

Suddenly, the guides shushed us. We crept along with as few cracks and rustles as possible, not knowing what to expect. The line came to an abrupt halt. "Look!" the guide whispered, pointing up into a particularly tall tree ten meters away. "There!"

We peered up into the tree, quietly fanning out in a circle around him. We kept peering. Nothing.

"There! Keep looking!"

A branch moved. A brown hand reached out from the leaves and snatched a piece of fruit. Another minute passed. Then with a rustle, the full chimp emerged, glanced in our direction, dropped like lightning out of the tree, and scampered off through the brush.

No one said anything.

"Okay," said the guide. "It is time to go back."

On the way home, we stopped and saw another chimp hand reach out from a treetop perch on the other side of the valley to pick a piece of fruit. This was the moment when my legs, crushed beyond recognition after, among other things, cushioning the fall of a fully grown man, stopped working. I told the party to leave me behind and save themselves.

Somehow, after finding a paved road and landing a ride, miraculously in the correct cardinal direction (although also on the back of a flat bed truck, which would have given me a full blown anxiety disorder had I not been semi-conscious), I made it back to Park HQ. On the way home to Kigali, I dozed and stewed in a savage disappointment over the yield.

Until one week later, when I stopped limping, and when I learned that it took Jane Goodall three months before she saw her first chimp in the wild.

The most obvious reason to visit Rwanda is to see the world's most fascinating primates in their natural habitat - a quixotic quest if ever I've experienced one. For anyone with a few days to spare after tracking mountain gorillas, Nyungwe Forest offers a small primate B-side.

Monkeys are the most visible residents of the forest. Families of L'Hoest monkeys pick through vines in the roadside tangles of brush, and a troop of Colobus monkeys on the nearby tea estate has been habituated to refrain from fleeing when park visitors come crashing through the undergrowth.

Monkeys are the most visible residents of the forest. Families of L'Hoest monkeys pick through vines in the roadside tangles of brush, and a troop of Colobus monkeys on the nearby tea estate has been habituated to refrain from fleeing when park visitors come crashing through the undergrowth. But chimpanzees are the attraction that draws most primate-watchers to Nyungwe. For seventy US dollars, you can attempt to track them with the help of a guide, a handful of trackers, and a walkie-talkie. This experience is best suited for hikers who feel a twinge of excitement at the thought of waking up at 4:30 am, scrambling around a rainforest in pursuit of the most elusive of primates, and emerging from a green world, half a day later, crippled and completely covered with mud.

Chimp treks differ from normal Nyungwe hikes because there are no pre-cut trails that allow you to follow the chimps' erratic movements. The terrain is extremely steep; and because Nyungwe is a true rainforest, the ground cover is both exceptionally dense and sopping wet. The result is an experience that, when retold in later company, sounds like a journal entry of an early American pioneer: the journey was muddy, daunting, backbreaking, and occasionally meaningful.

A tracker with a machete begins the procession, hacking through the thickest vines and branches. The guide follows, indicating which entrances to small mammal burrows could potentially snap a leg if accidentally plunged into. Civilian hikers bring up the rear, wielding long, thin walking sticks. They plunge through thick curtains of ferns, ducking under vines, climbing over fallen tree trunks, ice-skating across the slippery sides of the hills, all the while trying to ignore the furry white caterpillars, black beetles, and other unnaturally large insects resting on the leaves that brush over their faces and necks.

Traveling with speed is, unfortunately, impossible. Therein lies the challenge. Chimps prefer to take their breakfast in the valleys that lie between hills. They will tolerate the presence of a tracker or two; but when the number of gawkers rises above comfort level, they swing over to the next valley, floating through the mountain treetops as effortlessly as butterflies.

Humans are a hopelessly grounded species. When the chimps disappear over the top of the next mountain, the only way to follow is to crawl up and down the hills in sluggish, groaning pursuit. The uphill slopes are steep enough that you can touch your nose to the trail without leaning forward more than a foot. Grabbing vines and pulling yourself up is the only way to steady your climb when the mud gives way.

Uphill may be slow and strenuous, but downhill makes people fall. Cover a wall in your house with vines and mud, and then walk down it. If you can do it without bruising the end of your spine when you slip, or overextending leg muscles when one foot gets hung up in the foliage and the other slides out from under you, then chimp tracking will come naturally to you.

After four hours of climbing, sliding, falling, and being scratched by thorns, all the while hearing the screams of chimps around every next bend, the front tracker informed our group for the tenth time that we had just missed them. We mutinied. How were six people hacking through brush ever going to sneak up on such quick animals? We wanted to turn back, we declared. Because park policy is to refund the tracking fee if no chimps are spotted, the guides huddled and began to whisper. After a few minutes, one of them assured us that if we did not see a chimp around the next bend, we would turn back. We were a group of strangers thrown together in the woods, and we did not have a unity of purpose. No one wanted to be the wimp who made everyone turn back twenty minutes too early. We set off again.

Another stretch down, more slipping, more thorns. The guide behind me fell and took me out. Like amateur skiers, we both tumbled down to the swampy creek at the bottom. Then another aching uphill. A vine I grabbed ripped out of the ground and sent me flailing backwards for a few yards.

Suddenly, the guides shushed us. We crept along with as few cracks and rustles as possible, not knowing what to expect. The line came to an abrupt halt. "Look!" the guide whispered, pointing up into a particularly tall tree ten meters away. "There!"

We peered up into the tree, quietly fanning out in a circle around him. We kept peering. Nothing.

"There! Keep looking!"

A branch moved. A brown hand reached out from the leaves and snatched a piece of fruit. Another minute passed. Then with a rustle, the full chimp emerged, glanced in our direction, dropped like lightning out of the tree, and scampered off through the brush.

No one said anything.

"Okay," said the guide. "It is time to go back."

On the way home, we stopped and saw another chimp hand reach out from a treetop perch on the other side of the valley to pick a piece of fruit. This was the moment when my legs, crushed beyond recognition after, among other things, cushioning the fall of a fully grown man, stopped working. I told the party to leave me behind and save themselves.

Somehow, after finding a paved road and landing a ride, miraculously in the correct cardinal direction (although also on the back of a flat bed truck, which would have given me a full blown anxiety disorder had I not been semi-conscious), I made it back to Park HQ. On the way home to Kigali, I dozed and stewed in a savage disappointment over the yield.

Until one week later, when I stopped limping, and when I learned that it took Jane Goodall three months before she saw her first chimp in the wild.

Wednesday, March 01, 2006

Primeval Playground

Nyungwe Forest

Rwanda's Nyungwe Forest is like an old man. Every inch of its thousand square kilometers is hunched, twisted, and tangled.

Rwanda's Nyungwe Forest is like an old man. Every inch of its thousand square kilometers is hunched, twisted, and tangled.

Nyungwe is a true rainforest, so damp fog and overcast skies are the norm, apart from the moments when afternoon sun breaks through the cloud cover. A mountainous snarl of old trees and dense greenery carpets its gaspingly steep slopes.

Entering the park is startling. One second you are cruising between the usual crowded red-clay hills, and the next you are plunged into the cool thickness of trees. Suddenly, the laughter of children being let out of school is replaced by the piercing whine of insects. Thousands of trees - bare and broken, thick and leafy, young, ancient, all as green as emeralds - stand out against the gray of the sky.

It takes over an hour to drive through the park. For most of the trip, the road is deserted. (This is a novelty in an otherwise densely populated Rwanda.) The dripping silence is broken only by the appearance of black and white l'Hoest monkeys munching on the new shoots of roadside vine growth, and the presence of camouflaged soldiers patrolling the perimeter. The latter are more sociable than the former, and wave hasty greetings to travelers. The monkeys, on the other hand, happily endure the loud rush of cars and trucks zooming past, but they run off in terror the second a driver slows down to look at them.

My Dinosaur Swamp

Nyungwe boasts a color-coded network of easily navigable trails. Within walking distance are waterfalls, troops of semi-habituated monkeys, mountains, valleys, rivers, and a working tea plantation.

One trail leads to the Kamiranzovu swamps, an entirely unique ecosystem. The most shocking moment I experienced in Nyungwe was, after winding up and down claustrophobically tree-covered mountains for forty minutes, rounding a bend and watching a far off swampland open up in front of me. Every dinosaur-themed movie I saw as a child came back to me. Its appearance is so prehistoric that it is otherworldly in its foreignness, like a display in a natural history museum. If a pterodactyl had swooped down from the mountain crags overhead, I would not have been surprised. Instead, a family of l'Hoest monkeys ran across the road and scrambled up a huge mahogany tree, chattering warnings at me.

Rwanda's Nyungwe Forest is like an old man. Every inch of its thousand square kilometers is hunched, twisted, and tangled.

Rwanda's Nyungwe Forest is like an old man. Every inch of its thousand square kilometers is hunched, twisted, and tangled. Nyungwe is a true rainforest, so damp fog and overcast skies are the norm, apart from the moments when afternoon sun breaks through the cloud cover. A mountainous snarl of old trees and dense greenery carpets its gaspingly steep slopes.

Entering the park is startling. One second you are cruising between the usual crowded red-clay hills, and the next you are plunged into the cool thickness of trees. Suddenly, the laughter of children being let out of school is replaced by the piercing whine of insects. Thousands of trees - bare and broken, thick and leafy, young, ancient, all as green as emeralds - stand out against the gray of the sky.

It takes over an hour to drive through the park. For most of the trip, the road is deserted. (This is a novelty in an otherwise densely populated Rwanda.) The dripping silence is broken only by the appearance of black and white l'Hoest monkeys munching on the new shoots of roadside vine growth, and the presence of camouflaged soldiers patrolling the perimeter. The latter are more sociable than the former, and wave hasty greetings to travelers. The monkeys, on the other hand, happily endure the loud rush of cars and trucks zooming past, but they run off in terror the second a driver slows down to look at them.

My Dinosaur Swamp

Nyungwe boasts a color-coded network of easily navigable trails. Within walking distance are waterfalls, troops of semi-habituated monkeys, mountains, valleys, rivers, and a working tea plantation.

One trail leads to the Kamiranzovu swamps, an entirely unique ecosystem. The most shocking moment I experienced in Nyungwe was, after winding up and down claustrophobically tree-covered mountains for forty minutes, rounding a bend and watching a far off swampland open up in front of me. Every dinosaur-themed movie I saw as a child came back to me. Its appearance is so prehistoric that it is otherworldly in its foreignness, like a display in a natural history museum. If a pterodactyl had swooped down from the mountain crags overhead, I would not have been surprised. Instead, a family of l'Hoest monkeys ran across the road and scrambled up a huge mahogany tree, chattering warnings at me.