Touring the Lakeside Town of KibuyeTwo posts ago, I described the bus ride to Butare - compared to riding mini-taxis in Kigali - as hair-raising. I had the foresight (or perhaps the pessimism) to qualify my fear by finishing the paragraph with this sentence:

But I haven't even been to the north at this time, so I'm sure driving on the sides of volcanoes will rearrange my perspective yet again.I still haven't been to the north, but I have now been out west. As prophesied, the rides on public transport just get crazier as the elevation increases.

The town of Kibuye is on Lake Kivu, the large body of water that separates Rwanda from the DRC. The entire country of Rwanda gets higher as you move west, so the elevation of Kibuye is about 1000 feet higher than Kigali. That means a trip through the mountains to get there.

There is no such thing as a straight line on the Kibuye road. It follows the most curvaceous route possible, winding up and down through the mountains. The road was built by Chinese laborers in the 1990s and is described in our guidebook as "a marvel of engineering." There are positive aspects, I agree: the road is evenly paved tarmac; there are some rock walls to protect against rockslides; and it is complete. But it is only two lanes, which encourages the practice of overtaking around blind curves. Also, the drainage ditches are really deep, which is great in theory - except that they run right next to the road for the duration, so there is rarely more than six inches of shoulder.

In the US, mountain roads have metal guardrails running beside cliff edges. Whether or not they will prevent a car from rolling over the edge is debatable, but they definitely have a degree of protective value. Some Rwandan roads have similar metal rails beside the high stretches, and some have rows of concrete blocks around extremely tight curves. The Kibuye road has neither. A line of skinny white poles, each about 8 feet away from its neighbor, occasionally appears to point out severe bends. A few were ripped in half, which suggests they are plastic. These poles have a warning function only. If they were more tightly packed, they would do more good, but a car could run right between them if it lost control.

The Kibuye road is absolutely adequate for conscientious drivers. We didn't have one on our first trip.

Enough To Make a Nun PrayBudget travelers in Africa are often confronted with the internal conflict that comes with taking public transport. On one hand, it is dirt-cheap, usually 1 to 3 dollars. On the other, the ride can range from uncomfortable to dangerous if the driver is not reliable. We chose to take an Okapi Tours and Travel mini-taxi from Kigali to Kibuye and have no desire to repeat the experience (see BLOG). The driver drove much too fast for the conditions, especially when it began to rain. He drove on the wrong side of the road around blind curves, overtook when it was too risky, and generally disregarded all passenger comfort in his quest to get us there in two hours.

I was not the only nervous person this time. Some of the Rwandan passengers were nervous, too. The first hour was comfortable, but about 30 km past Gitarama it started to rain. The temperature dropped ten degrees, and the road began to snake upwards into the clouds. On Rwandan roads, mini-vans always struggle to the top of hills, and then coast down to the bottom in order to build speed for the next uphill stretch. I expect these bursts of speed because they make it easier on the vans to crawl up to the peaks. But our driver hit the accelerator as soon as the downhill sprints started, and the vehicle began to take the curves at breakneck speed. Remember that there are no straight lines on this road, so we were tossed back and forth relentlessly.

Several women stopped their conversations, leaned forward, and closed their eyes. The nun sitting in front of me began to pray. I removed my headphones and sat up. The whole vibe in the bus had changed from jovial to tense. The volcanoes loomed in the distance, and a chilled wind whipped in through the open windows. One woman had to ask to pull over so she could be sick.

After 20 more kilometers of being thrown around, we finally decided to speak up since no one else was. We yelled over the hum of the rain for the driver to slow down, startling many people out of their private reveries. After much confusion, one passenger decided that we were worried about getting a speeding ticket. "I believe you are afraid of the police!" he giggled. Suddenly, the ice was broken. The whole bus erupted in conversation about us, and our request was forgotten as we zoomed along. My only solace came when the nun stopped praying and took a cell phone call.

Alighting in Kibuye was pure joy. I muttered maledictions under my breath, hauled my pack onto my back, and trounced off down the muddy road to find a hotel.

The Buzz on the BethanieThe budget Catholic guesthouse was full that night because of a conference. On foot, tired, and stressed from the ride, we hiked for another rainy hour until we found a room at the secluded Bethanie Episcopal Centre. Luckily, Kibuye is beautiful:

dripping pine forests and blue-green lake on all sides. The hills all slid right down into the water, and the only sounds came from bleating goats and cheeping birds. As evening crept in, we settled into the solitude of the forest - the budget rooms were set down the drive from the rest of the hotel - ate dinner, and went to bed.

As I sleepily fumbled with my toothbrush, I noticed the dull throb of buzzing insects somewhere over my head. A large swarm of insects, from the sound of it. I knew there was a fluorescent lamp right outside the front door, and I figured the sound was coming from noisy beetles it must be attracting. There were screens on the windows, so I was not concerned.

At five the next morning the call to prayer from a nearby mosque jarred us awake, so we decided to get an early start on exploring. The same humming noise continued as we got ready, but when we opened the door to leave, there were no bugs flying around. I shined my headlamp on the outside light. It was crawling with honeybees. Dead bees littered the concrete porch, and more were drunkenly attached to the door. Hastily, I locked it and made a mad dash to the drive. They must have been up all night, which struck me as highly unnatural. The reception attendant sounded defeated when we told her that the rooms in the budget wing of the hotel were infested with crazy bees. "You cannot make them leave," she sighed, and offered us a choice of several other rooms that had smaller hives in their ceilings. We checked out.

Walking Around KibuyeEarly morning was my favorite time in Kibuye. A new hiking trail has been cleared around the Bethanie Centre peninsula, and it is perfect for watching all the

fishermen return from a long night of fishing out on the lake. As they row across the still water in their wooden canoes, their songs carry for miles. The singing is beautiful; it reminded me of the kind of crying that results from genuine relief.

Most visitors to Kibuye attend conferences or church gatherings, and the town does not really cater to the casual visitor. There is no taxi service except for motorcycle and bicycle rides, and each of the three hotels is a substantial walk away from each other. We walked for hours each day, and we soon discovered that the rain on the first afternoon afforded us a privacy that we never had again. Kibuye is a small town, and small towns everywhere have quirky attitudes towards outsiders. Westerners are not nearly as common there as they are in Kigali, and they do not normally walk around on foot. The local people were definitely surprised to see us as we wandered around. We were not unwelcome, but we did attract a lot of attention. This did not always make for the most relaxing of strolls.

The children of Kibuye provided an x-factor worth mentioning. There are always unsupervised kids wandering around in Rwanda, but I noticed many more of them in Kibuye than in other places. Some exhibited a sweet, friendly curiosity. More than one performed an impromptu song and dissolved into shy giggles as we walked by. But some - usually gathered into groups of six or eight - were poorly behaved around strangers. We were occasionally mobbed by these diminutive gangs, and when that happened one child always felt emboldened enough by the hubbub to show off by touching the white woman. One even grabbed my arm and shoved a half-eaten apple into my face, yelling at me to eat it. I soon found myself tensing up whenever I spotted children beside the road, as their reactions varied from politely wishing me a "bonjour" to physically accosting me.

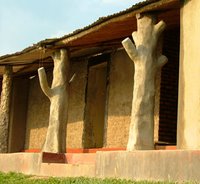

The Home St. JeanAfter the Bethanie bee incident, we walked all the way back up through town to the budget Home St. Jean to see if they had any vacancies. This guesthouse has a split personality. It is the cheapest place to stay in Kibuye, boasts wonderful views,

and is convenient to town, sitting up on a wooded hill adjacent to the Genocide Memorial Church. It also has what a guidebook would call 'local flavor.' As we approached, we watched men repairing cars in side lots and boys herding goats down the back driveway. A large troupe of schoolchildren paraded by, singing.

But the Home is also very shabby and has inadequate service. The water heaters were all unplugged, so there was no hot water. The shared bathrooms were grim, and the rooms were on the musty side. Most importantly, though, there was rarely any staff to be found; a child always had to go run and find the receptionist if you needed anything. There is no restaurant, and kitchen staff was scarce. Ironically, the place is always bustling with people, but very few of them are actual guests. I think church officials live in a rear building, and that might be why the staff never manned their front posts. I definitely got the impression that local people were catered to more than customers.

The first sight that greets you upon arrival is a burned out Toyota Land Cruiser.

The story we heard from Catholic Relief Services employees in Kigali is that this truck belonged to one of their employees who was staying at the guesthouse. Supposedly, one of the watchmen carefully siphoned the vehicle's gasoline out into a plastic bag in the middle of the night. Because it was so dark, though, he dropped the bag and spilled the gas everywhere.

Without thinking, he lit a match and held it underneath the body so he could see what happened. The truck promptly blew up.

In the evening, we were told that the kitchen was open for business but that we would have to wait to be served. After some sleuthing, I spied a group of church people dining in the rear, so I surmised they were being served first. That would have been a tolerable arrangement, except that the dinner guests turned their children loose to run around the hotel while they enjoyed their meal. Naturally, the herd of little barbarians made a show of provoking the mzungu who were waiting on the patio to eat. They would creep around the corner, sidle up to our table, yell all kinds of greetings, touch my arm, and then run away. This routine was repeated every ten minutes. As service is not top priority at St. Jean, we endured their attentions for over an hour. The only way to make them leave was to completely ignore them; and, needless to say, it is difficult to ignore a group of ten kids all yelling "Good Morning!!" in your ear at eight in the evening. After what seemed like an eternity, the adults began to emerge from the back house after their supper, and the aggravating scamps magically transformed back into angels as soon as the authorities appeared.

Dinner was delicious when it finally arrived: rice, beans, celery soup, plantains, and lots of peace and quiet.

Riding HomeWe got a ride in a private car back to Kigali. Compared to riding with Okapi, it was night and day. Now I understand why so many authors have written about the pleasures of driving in Rwanda: they were not taking public transportation. Having a patient driver makes all the difference in the world. When you secure a stress-free ride, it is impossible not to marvel at the Rwandan countryside.

Bird life is the dominant feature at Jambo Beach on Lake Muhazi. This small lake is a pleasant hour's drive east from Kigali, and the landscape is radically different from the west side of the capital. As you approach Tanzania, the hills are pulled much flatter and the landscape morphs into savannah scrublands. I must emphasize once more how beautiful Rwanda is from the window of car when one has a reliable driver and uncrowded roads.

Bird life is the dominant feature at Jambo Beach on Lake Muhazi. This small lake is a pleasant hour's drive east from Kigali, and the landscape is radically different from the west side of the capital. As you approach Tanzania, the hills are pulled much flatter and the landscape morphs into savannah scrublands. I must emphasize once more how beautiful Rwanda is from the window of car when one has a reliable driver and uncrowded roads.

Bird life is the dominant feature at Jambo Beach on Lake Muhazi. This small lake is a pleasant hour's drive east from Kigali, and the landscape is radically different from the west side of the capital. As you approach Tanzania, the hills are pulled much flatter and the landscape morphs into savannah scrublands. I must emphasize once more how beautiful Rwanda is from the window of car when one has a reliable driver and uncrowded roads.

Bird life is the dominant feature at Jambo Beach on Lake Muhazi. This small lake is a pleasant hour's drive east from Kigali, and the landscape is radically different from the west side of the capital. As you approach Tanzania, the hills are pulled much flatter and the landscape morphs into savannah scrublands. I must emphasize once more how beautiful Rwanda is from the window of car when one has a reliable driver and uncrowded roads.